Monthly Archives: October 2011

The idea of (im)mobility in the work of Emily Jacir

For Palestinians it is generally complicated to explain where they are from, as their places of origin are beyond reach or no longer exist as Arab towns and villages. Lod was an Arab town named Lydda, also Ramleh whose 60,000 inhabitants were expelled by Israeli forces in 1948, when Israel’s war of statehood began. During the Palestinian-Israeli conflict around 780,000 Palestinians were exiled from their homeland and dispersed across all over the world; stateless refugees whose number has grown to over four million. “If I could do anything for you, anywhere in Palestine, what would it be?” This question posed the Palestinian American artist Emily Jacir to Palestinians, who are both, denied entry or restricted to move freely in their land, for her highly regarded project Where We Come From (2002-2003). As the artists Mona Hatoum and Rashid Masharawi, Jacir deals with the Palestinian diaspora and her work emerges from personal experiences passing through places and crossing borders. By her neo-conceptual artworks and performances, which are based on photo-text presentations, task-based performances or the use of media and newspaper advertisements, Jacir’s work speaks about what it means to be a Palestinian today, both in the context of exile and living under occupation. How movement through places and cultures, either voluntary or forced, is reflected in her work, shall be looked at in detail, by examining the idea of (im)mobility in Emily Jacir’s work. T.J. Demos essay Desire in diaspora is used as a main source, along with the exhibition catalogue Emily Jacir – belongings: Arbeiten/Works 1998 – 2003 including an interview with Jacir by Stella Rollig and with contributions from John Menick, Edward W. Said and others.[1] With reference to a selection of Emily Jacir’s works from earlier projects, such as Change/Exchange (1998), along with Crossing Surda (2002) and From Texas with Love (2002), to her later artwork Where We Come From (2002-2003), I will analyse the idea of (im)mobility as the ability or inability to move freely or under compulsion.

In 1998, while in residence at the Cité Internationale des Arts in Paris, Emily Jacir produced Change/Exchange, which can be seen as a thematic starting point for much of her following works and a departure from her earlier painting and sculpture.[2] In her project Jacir traded one hundred American dollars for French Francs, losing a small amount to currency exchange rates, then converted the Francs back into dollars, and repeated this process until the sum, after sixty-seven times exchange fee, was completely exhausted. The piece, documenting the repeated exchange until only $ 2,45 in coins remained that no agency was willing to accept for conversion, displays photographs of the currency exchange offices paired with receipts of the transactions. Based on a simple neo-conceptual system Jacir’s project visualizes the economical loss caused by capitalist exchange rooted in dilemmas of travel and crossing international borders. Besides, the currency exchanges are ‘portals for global economy of continual transactions,’ as T.J. Demos has appropriately described.[3] Exchange and passing borders is never free and their costs differ from location to location. By a rudimentary currency exchange Jacir illustrates a back and forth relating to movement through places, border crisscrossing and migration, which also becomes a subject matter of the artist’s subsequent works that deal with it only more personal and political.

In My America (I am still here) (2000), which derived from a similar concept as Change/Exchange, Jacir bought several goods from every store at the World Trade Center Mall and later returned her purchases. Now, an unlimited back and forth seems to be possible. Photographs present these goods and the shopping bags together with receipts of the full refund of Jacir’s thirty-three purchases and returns. This artwork may reveal certain advantages of living in America that allow one to realize consumerist fantasies of infinite mobility and live them out. Yet, Jacir’s parenthetical statement ‘I am still here’ may thus express the impossibility or undesirability of other returns, as she is still in America.[4] Both pieces operate with repeated exchange that visualizes the commodities’ ability of free and infinite movement through global markets and across international borders, whereas individuals are restricted and denied entry into their homelands and certain territories. By contrasting forms of easy exchanges Jacir points out the human beings’ restricted freedom of movement caused by political instrumental barriers as the authorities of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict induce, and simultaneously emphasizes the absurdity of such barriers.

Traveling from one place to another and living in two different cultures are central to Jacir’s life that is also reflected in her work: The series of drawings From Paris to Riyadh (Drawings for my mother) (1999-2001), consisting of white vellum paper marked with black ink abstract forms that may be associated with patterns for garments of paper dolls, yet correspond to the exposed skin of the models in an issue of the “Vogue” magazine. The work stems from an autobiographical experience and a simple matter of fact to bring the magazines into the country. While traveling by plane to Riyadh in Saudi Arabia, where Jacir’s family lived during her childhood, her mother would have to censor the illegal sections of her fashion magazines, lest airport inspectors confiscate them. Ironically, the black patterns call attention to the allegedly appealing parts of the female bodies instead of hiding them. Many spectators mistakenly viewed the drawings as a critical commentary on the repression of Middle Eastern Woman, but for Jacir this work reflected negatively on both, the Eastern and Western society. She has stated it is about the equally discomfort and suppression, which she has felt in both places: ‘Being back and forth between these two spaces – one of commodification’ and objectifying the image of woman and ‘the other of banning the image of the female body.’[5]

Further, as an aspect of movement through spaces, Emily Jacir meditates the effect of travel restrictions. The video Crossing Surda (a record of going to and from work) documents Jacir’s daily twenty-minute walk across the infamous Surda checkpoint manned by Israel military to get from her home in Ramallah to Birzeit University, where she was teaching. Intended to do a recording for herself, she cut a whole in her bag and clandestinely filmed her quotidian commute for eight days. The recorded travel brings the spectator through a landscape of several concrete barriers, often marked with the Israeli flag, and occasionally shows ordinary Palestinians’ encounters with Israeli soldiers. Based on her own and many Palestinians’ experience Crossing Surda exposes the frustration provoked by endless checkpoints and the loss of hours by crossing those border controls. This artwork provides an account of the humiliating conditions ordinary individuals endure under occupation. Besides, the recording particularly reveals the prohibition on the representation of such checkpoints.[6]

As an experience very different from living in Palestine with an oppressive system of Israeli roadblocks and controls, in the video From Texas with Love Emily Jacir drives one hour freely through the Texan landscape wherever she desires to go without being stopped and listens to music.[7] Jacir directed this artwork to Palestinians under occupation and posed them the question: “If you had the freedom to get in a car and drive for one hour without being stopped (imagine no Israeli military occupation; no Israeli soldiers, no Israeli checkpoints and roadblocks, no ‘bybass’ roads), what song would you listen to?” The selected fifty-one songs were very different: some amusing, some melancholy, including American pop music, as well as Arab nationalistic hymns.

As an experience very different from living in Palestine with an oppressive system of Israeli roadblocks and controls, in the video From Texas with Love Emily Jacir drives one hour freely through the Texan landscape wherever she desires to go without being stopped and listens to music.[7] Jacir directed this artwork to Palestinians under occupation and posed them the question: “If you had the freedom to get in a car and drive for one hour without being stopped (imagine no Israeli military occupation; no Israeli soldiers, no Israeli checkpoints and roadblocks, no ‘bybass’ roads), what song would you listen to?” The selected fifty-one songs were very different: some amusing, some melancholy, including American pop music, as well as Arab nationalistic hymns.

Jacir has stated about From Texas with Love: ‘The piece was about being in a place so incredible and beautiful and being able to drive freely and to listen to music, and at the same time wanting to cry, because this cannot happen back home.’[8] Her artwork expresses on the one hand freedom in mobility, yet at the same time exposes the reality that Palestinians are not able to move freely through their homeland and the video imagines only a ‘momentary fantasy’[9] of freedom in Palestine, as one watches a video recorded in an American state. The expression of entire freedom thus dramatizes an extensive unfreedom.

Emily Jacir’s artistic work culminates in her project Where we come from (2002-2003), which is concerned with the possibility or impossibility of movement. The piece is linked deeply with Jacir’s personal life as she has explained in an interview with Stella Rollig: ‘it is coming from the experience of spending my whole life going back and forth between Palestine and other parts of the world. I am always taking things back and forth for other people.’[10] Her ability to move relatively freely in Israel, as an American passport holder, leaded Jacir to her action to help Palestinians – both those in exile who are forbidden entry into their homeland, as well as those who are living under occupation – by asking them if she could do anything for them, anywhere in Palestine and promised to realize their desires. The responses ranged from simple practical requests, such as playing soccer with a Palestinian boy or paying a phone bill, to highly emotional pleas as going on a date with a Palestinian girl that the exile has only spoken to on the phone. One man demanded: “Go to my mother’s grave in Jerusalem on her birthday and put flowers and pray.” A snapshot of the mother’s grave with its tombstone shadowed by Jacir’s shape documents, together with the man’s request in Arab and English in black lettering on a white panel next to the colour photograph, Jacir’s fulfilling of the man’s wish. A short notation under the request tells the spectator that the man, Munir, lives only a few kilometres away in Bethlehem, but was denied entry to Jerusalem by the Israeli authorities. Jacir could go to his mother’s grave instead: as an agent of fulfilling desires Jacir acts as a vehicle for the wishes of others, yet her visit remains vicarious and phantasmic.

Movement in terms of travel, migration or translation even only desired is deeply concerned in this project: The spectator faces the diptychs divided into one text panel and one photograph. The visual transition from language to image seems effortless, with one shift of the eyes from the request to its photographically captured actualization. Yet, for many unfortunate just this translation from desire to fulfillment, which we often take for granted, persist unachievable and thus can only be imagined and wished.

This project reflects on the condition of exile by Jacir’s engagement with the idea of deterritorialisation in artistic practices of the 1990s, drawing from the premise of site specificity, which is central to conceptualist practice and reconfiguring them in the context of the history and presence of Palestine. Edward W. Said has stated that exile is a ravaging experience and represents ‘the unhealable rift between a human being and a native place, between self and its true home.’ A gap that separates one from ‘the nourishment of tradition, family, and geography.’[11] For exiles, there does not exist site specificity, as they have been displaced from their homelands and forced to move through places as refugees. According to T.J. Demos the impossibility of sitedness for exiles is one of the consequences why Jacir has rejected site specific work, which means that an art object is dependent for its impact or meaning on a particular place in which it is sited. Obviously, the Palestinian diaspora and its conditions, in a legalistic, political, economical and cultural sense, are the subjects Jacir investigates, and which resist any geographical delimitation. Besides, Jacir’s ‘fragmentational’ work including the use of a variety of mediums, such as photography, text and video, along with her use of distribution systems, as museums, galleries and media like newspapers and internet and also her choice of different sites as Israel/Palestine and New York refuses any kind of site specificity.[12] Jacir’s project thus is characterized by displacement and far from the possibility of sitedness.

By analyzing a selection from earlier to later artworks, I have sought to exemplify the idea of (im)mobility in the work of Emily Jacir that derives from her own experiences of moving through spaces and traveling from one place to another as an Palestinian exile. In her earlier works, such as Change/Exchange and My America (I am still here), Jacir points out the ridiculousness of barriers on people’s lives, caused by political authorities, by visualizing simple repeated exchanges and contrasting the inequality between individuals’ unfreedom of movement and the free mobility of commodities as products of the capitalistic world. These early projects deal with the Palestinians’ life with its condition in a more indirect way than Jacir’s following artworks: The autobiographical work From Paris to Riyadh (Drawings for my mother) emerged from personal experiences and describes mobility as a back and forth between two places, Paris and Riyadh, and their different cultures. At the same time it can be seen as a criticism of both, Western and Eastern societies that either treat the image of women as a commodity or ban the image of a female figure. Jacir’s projects are often related to each other and thus dramatize the impossible mobility of unfortunate Palestinians, as exemplified with Crossing Surda, which documents the effect of travel restrictions and From Texas with Love that is directed to Palestinians living under occupation and represents a fully freedom of mobility in America in order to point out the unfreedom of many Palestinians. The last analyzed project Where We Come From concerns Jacir’s freedom of mobility as an American passport holder in contrast to the unfortunate Palestinians who are refused to live freely and interact or participate in the world like others.

[1] Demos, 2003 and Rollig/Rückert, 2004, see bibliography.

[2] Menick, p. 26.

[3] Demos, p. 72.

[4] Demos, p. 75.

[5] Interview with Stella Rollig, p. 19.

[6] Demos, p. 67 and Finkelpearl/Smith, p. 75.

[7] Jacor developed this work when she was in West Texas for a residency.

[8] Rollig, p. 18.

[9] Menick, p. 31.

[10] Rollig, p. 9.

[11] Said ‘Reflections on Exile,’ Granta 13 (Autmun 1984), cited in Demos, p. 69.

[12] Demos, p. 69.

Bibliography

Baur, Andreas/ Roland Wäspe. Emily Jacir (exh. cat., Kunstmuseum St. Gallen/ Villa Merkel, Galerien der Stadt Esslingen am Neckar). Nürnberg, 2008.

Demos, T.J. ‘Desire in Diaspora: Emily Jacir,’ in Art Journal (Winter 2003): pp. 68-78.

Finkelpearl, Tom/Smith, Valerie. Generation 1.5 (exh. cat., Queens Museum of Art). New York, 2009.

Menick, John: ‘Undiminished Returns: The work of Emily Jacir, 1998 – 2002’, in Emily Jacir: Belongings: Works, 1998-2003, eds. Rollig, Stella/ Rückert, Genoveva, pp. 20-45. (exh. cat., O.K. Centrum, Linz). Linz, 2004.

Rollig, Stella: ‘Emily Jacir – Interview,’ in Emily Jacir: Belongings: Works, 1998-2003, eds. Rollig, Stella/ Rückert, Genoveva, pp. 6-19. (exh. cat., O.K. Centrum, Linz). Linz, 2004.

Said, Edward W.: ‘Emily Jacir – Where We Come From’, in Emily Jacir: Belongings: Works, 1998-2003, eds. Rollig, Stella/ Rückert, Genoveva, pp. 46-49. (exh. cat., O.K. Centrum, Linz). Linz, 2004.

The relationship of text and image in John Baldessari’s work

The American conceptual artist John Baldessari became popular in the 1960s and has reached a broad influence on younger generations. His work is characterized by a wide variety of mediums including photography, video, painting, texts, prints, film, drawing and books. Baldessari is passionate about language that is reflected in his oeuvre. His work shows an intensive interest in written and visual language that is expressed in compositions of text and image as equal elements. How does the artist use these two components and how are they connected to each other, are questions which shall be looked at in detail by discussing the relationship of text and image in John Baldessari’s work. The artist’s treatment of language and his text-image combinations is the subject of many researches, notably Russell Ferguson’s essay about Baldessari as the Unreliable narrator[1]. With reference to a selection of Baldessari’s artworks from the late 1960s to his recent pieces, I will examine the relation of text and image. An analysis will first be made of Baldessari’s early text and photo paintings from 1966 to 1968, and then examples from the 1980s onwards will be analysed in order to compare and discuss the function of text and image in Baldessari’s work.

In the late 1960s Baldessari neglected painting and started to use words as a compositional element as images. ‘A word can’t substitute for an image, but is equal to it’, explained the artist in an interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist and stated further: ‘You can build with words just like you can build with imagery.’[2] He began to create artworks with pure painted text on canvas and emulsions of photo and text. From 1966 to 1968 Baldessari produced a series of text-paintings consisting of statements about art and its concept.[3] He displayed quotations from known art critics and used formulaic instructions or definitions and comments from art manuals.[4] Thereby the artist transformed the influence of art theory and critics on artworks to the motif of his conceptual text-paintings.[5] As an artist of the conceptual art movement Baldessari’s aim was to produce art without using the conventional art praxis. Thus text as a new form and its rapport with images began to gain importance for Baldessari and artists like Joseph Kosuth and Ed Ruscha.[6]

Although Baldessari chose text as the new media of representation, he still painted the words on canvas as a gesture of painting. Baldessari intended to ensure the artistic nature of these new works by using the canvas as an art signal.[7] In combining traditional components of painting, stretched canvas and paint, Baldessari sought to render the new art forms, namely text and photography acceptable as art and bring them into galleries and museums. [8]

Painting And Drawing, 1966-68. The Broad Foundation, Santa Monica. Acrylic on canvas. 67 ½ x 56 in. (Source: Jones/Morgan), p. 12.

Russel Ferguson argues that Baldessari is not primarily concerned with text as a compositional element, but rather with the ‘ambiguity of the relationship between textual and visual components’[9], which is the centre of attention in the artist’s work. Even if it seems that Baldessari uses the juxtapositions of text and image to create direct information for the audience, his artworks intend to arouse suspicion and doubt. The work Painting and Drawing pretends to deliver practical information for an art student on how to improve his work: “This painting contains all the information needed by the art student.” But the displayed text does not convey any useful information about how to draw and paint at all. This painting consists of a text introduced with a caption about the expected content of the writing. It is even represented as a book page, text on blank white background. This creates the impression of a replacement of an extract of a writing, which is supposed to deliver practical knowledge but only transfers a confounding message. Baldessari thus acts as a misleading informant, who is literarily characterised by Ferguson as the “unreliable narrator”. As this piece exhibits, text often appears as simple information but turns out to be more unreliable than trustful. It is used to subvert what the artwork shows us. What is Baldessari’s message? There exists no definite conclusion; the artwork is ambivalent. Contrariwise other text-paintings such as Tips for artists who want to sell give us the supposed ‘straight information’[10] as the caption promises. Here, by providing advice about colour, subjects and its matter, Baldessari tells us the best way, how to sell a painting. However, this statement about the content of pictures underlies a sophisticated impact of irony, and thereby again creates the previously mentioned notion of ambiguity.

Tips for Artists Who Want to Sell, 1966-68. The Broad Art Foundation, Santa Monica. Acrylic on canvas. 68 x 56 ½ in. (Source: Jones/Morgan), p. 12.

In Baldessari’s photocompositions, based on an experimental photoemulsion process, each image is accompanied by a single caption. Image and text interact, they elucidate and supplement each other.[11] For the series Wrong the artist matched photographs of himself with lucid statements in order to explain the right and wrong way of a photographical composition.[12] For example, one photograph shows Baldessari standing in front of a palm tree, which seems to grow out of his head. Regarding compositional correctness the picture demonstrates to the viewer an incorrect arrangement, which is underlined by the title “wrong”. The same idea forms the basis of The spectator is compelled…, whose caption carries on: “…to look directly down the road and into the middle of the picture.” In this photograph Baldessari is looking down the road with his back turned to the viewer, standing at the place that is the focus of the viewer’s gaze. Once again, it is a wrong composition because the spectator’s eye is led directly into the middle of the photograph.

Wrong, 1966-68. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles. Photoemulsion and acrylic on canvas. 59 x 45 in. (Source: Jones/Morgan)

The Spectator Is Compelled…, 1966-1968. The Broad Art Foundation, Santa Monica. Acrylic on canvas. 59 x 45 in. (Source: Jones/Morgan)

Not only the artist’s early work rather his whole oeuvre is a reflection of his interest in linguistic theories. For Baldessari, text and image are equal vehicles of the same linguistic system to transfer information. Their encounters establish an indefinite number of different meanings. When one image and one word, two words or two images abut oneach other, a new meaning comes to light with every combination. The work Kiss/Panic, consisting of a collage of photographs, provokes such multiple significations throughout the juxtaposition of several images.[13] Two central pictures that show contrasting settings: the upper one is a colour close up of an intimate kiss scene and the lower a crowded and chaotic place in black-and-white. They are surrounded by ten gray scale images of guns targeting outward. The imagery is dominated by a tension between the offered and converse feelings – panic and love. This artwork demonstrates how the meaning of an image can alter by hybridization with other images as vehicles of information, which function as tools of a larger system of language. In the same way words and text operate as part of Baldessari’s imagery. Meaning is exposed by their arrangements and through their surroundings.

Kiss/Panic, 1984. Glenstone. Black-and-white photographs and oil tint on board. 80 x 72in. (Source: Jones/Morgan)

Baldessari’s treatment of language as a system of signs originates from the influence of Structuralism.[14] In particular Ferdinand de Saussure and Claude Lévi-Strauss’s theories were sources for his work. Saussure’s perception that ‘the idea or phonic substance that a sign contains is of less importance than the other signs that surround it’[15] and Lévi-Strauss’ ‘practice of drawing structural connections between seemingly unconnected things’[16] affected Baldessari’s work in the sense that it describes a process of syntactical combination and an intentional contrasting of words and images creating his ambiguous collages.

In many artworks the relation of text and image is affected by interdependence between these two components. Baldessari’s Goya Series of the nineties and his more recent Prima Facie series reveal such interaction of written and visual language. For the Goya Series the artist returned to the text-and-image format of his earlier works. He juxtaposed black-and-white photographs of isolated banal modern and everyday objects, staged as still lifes with terse extracts derived from titles of Francisco de Goya’s disaster of war etching series, denouncing the horrors of violence. Some captions and their respective photographic items are, for instance: “And” combined with a paper clip; “There isn’t time” with a bouquet of flowers in a vase; and “Not so that you could tell it” with two balls. For this series Baldessari used Goya’s language in order to create his own imagery. In Goya’s series the captions understate his printed terrifying visions, yet, Baldessari established a balance between words and pictures: they possess the same equal value and importance.[17] In isolation both image and text are incomprehensible, but when combined they provoke the possibility of multiple readings.

Goya Series: There Isn’t Time, 1997. Private Collection. Courtesy of Häusler Contemporary Munich/Zurich. Ink-jet and acrylic on canvas. 75 x 60 in. (Source: Jones/Morgan)

Goya Series: Not So That You Could Tell It, 1997. Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York and Paris. Ink-jet and acrylic on canvas. 75 x 60 in. (Source: Jones/Morgan)

Goya Series: And, 1997. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Ink-jet and acrylic on canvas. 75 x 60 in. (Source: Jones/Morgan)

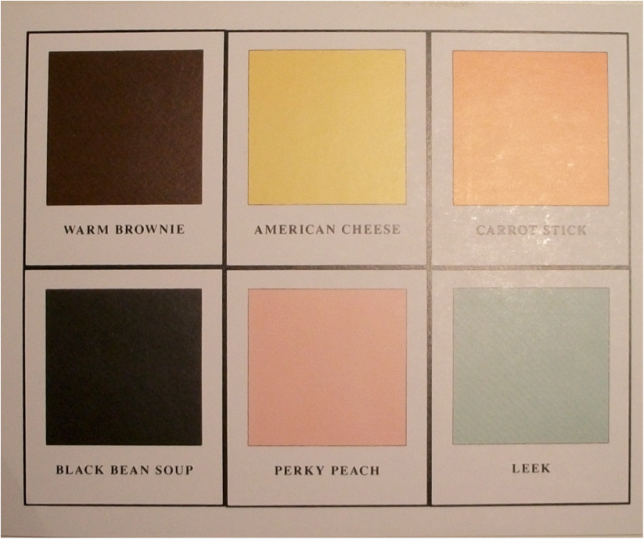

The text-word parity plays a significant role in Baldessari’s work: ‘I try to give equal weight to words and image, at least when they’re of equal importance to me.’[18] So Baldessari created the series Prima Facie, which is Latin and means “first evidence”. His first works for the series were diptychs, consisting of equal sized parts, on one side a word and on the other an image. Baldessari combined film stills, showing an actor’s facial expression, matched with a word. He sought to puzzle out what that person’s face might express and tried to find an appropriate word, which exactly describes that expression. The idea of this series was to detect a word as an equivalent for an image, to stress their equal weight.[19] Yet, Baldessari chose film stills and therefore acted emotions consciously. What we see is thus a faked emotion. By looking at someone’s face we may think we understand this person’s expression at the first glance, as the artwork is titled, but we could be entirely wrong. Baldessari’s investigations run over the whole series of five exhibitions, following through several states until the facial expression is replaced with a square of just pure colour. In Fresh Cut Grass/Frogs Belly/Lizard Green/Spinach colour comes into the pictures of the actors’ faces as a glaze over black-and-white photographs and is connected with pigmentary varieties arising from the earth. Warm Brownie/American Cheese/Carrot Stick/Black Bean Soup/Perky Peach/Leek is a combination of colours, which are chosen on the basis of food. After his semiotic games of interchangeable words and images, Baldessari is more concerned with the relationship of colour and image in these artworks from 2005.

- Prima Facie: Intent/Concerned, 2005. Courtesy John Baldessari and Margo Leavin Gallery. Archival digital print on ultrasmooth fine art paper mounted on museum board. Dimensions variable. (Source:http://xtraonline.org/past_articles.php?articleID=115#footnote, accessed: 5 January 2010)

Throughout Baldessari’s juxtapositions of text and image and their representation, the audience is committed to undertake the important role of interpreters. Baldessari makes an effort to give the audience a ‘bare amount of information that doesn’t asphyxiate the piece’[20], i.e. just enough to activate the mind. As discussed earlier, Baldessari uses his combinations of picture and image in order to transfer divers meanings and offer multiple interpretations. He seeks to propel the readers’ associations and ideas, trying to obtain interaction between the artworks and his audience. He invites the audience to take part throughout his artworks, as Weissman describes in an appropriate way: ‘These pictorial proposals, games and questions are begging for participation.’[21]

Prima Facie (Fifth State): Fresh Cut Grass/ Frogs Belly/ Lizard Green/Spinach, 2005. Leonard Rosenberg. Archival pigment prints on ultrasmooth fine art paper on museum board. 120 x 48 in. (Source: Jones/Morgan)

By analysing a selection of John Baldessari’s work from his early text-paintings, along with his Goya series of the nineties to his latest Prima Facie artworks, I have examined the usage of Baldessari’s juxtapositions of text and image and how they function. John Baldessari works with text and image as equal elements. Within the conceptual art movement during the sixties and seventies, text as a new media of representation began to play a decisive role. Baldessari combined the new, experimental form text, and also photography with conventional mediums as painting. Since then he has enjoyed to create a mixture of written and visual language to transfer divers meanings and multiple information. Text and image interact, they are able to elucidate, supplement or subvert each other. Baldessari is concerned with the effect of their combination and with the product of their mixture. ‘I’m not too interested in this word or that word, but in what happens between those two words when they meet.’[22] This quote reflects the artist’s interest in language as a system and the influence of structuralist thoughts of pioneers as de Saussure and Lévi-Strauss. His work possesses a semiotic structure, text and image are interchangeable vehicles of a larger linguistic system, and they propel multiple reading and interpretation of Baldessari’s work. The artist achieves to activate the audience’s associations and thoughts with the help of his juxtapositions of text and image. Baldessari’s work can literarily be described as a word-image game. As the ‘unreliable narrator’, he uses words and imagery, to mislead, to confuse, to surprise and to amuse his audience in order to provoke participation. In conclusion the relationship of text and image in John Baldessari’s work is divers.

As I have mentioned before and as the artwork Prima Facie (Fifth State): Warm Brownie/American Cheese/Carrot Stick/Black Bean Soup/Perky Peach/Leek shows, colour and its relation to language is another subject of interest for John Baldessari. There are many artworks like Color Card Series: Five Oranges (with Foot)[23] and the film Six Colorful Inside Jobs[24] that express the artist’s examination of colour in his work and which could be a further research topic.

Prima Facie (Fifth State): Warm Brownie/ American Cheese/ Carrot Stick/ Black Bean Soup/ Perky Peach/ Leek, 2006. Glenstone. Archival pigment prints and latex paint on Parrott water-resistant matte canvas. 92 x 114 in. (Source: Jones/Morgan)

[1] Ferguson, Russell. ‘Unreliable narrator,’ in John Baldessari: Pure Beauty, eds. L. Jones and J. Morgan, pp. 87-94. (exh. cat., Tate Modern). London, 2009.

[2] Quoted in Obrist, Hans Ulrich. John Baldessari. The Conversation Series 18. Köln, 2009, p. 14.

[3] Examples for the text-Paintings: Clement Greenberg; Tips for artists who want to sell (both 1966-68).

[4] Wood, Paul. Movements in Modern Art – Conceptual Art. London, 2002, pp. 31.

[5] Fuchs, Rainer. ‘Written paintings and photographed colors. Comments on John Baldessari,’ in John Baldessari. A different kind of order: Arbeiten 1962-1984, eds. R. Fuchs and Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien , pp. 15-46. Köln, 2005, p. 28.

[6] Quoted in Obrist, p. 14.

[7] Baldessari quoted in Jones, Leslie. ‘Art Lesson: A narrative chronology of John Baldessari’s life and work,’ in John Baldessari: Pure Beauty, eds. L. Jones and J. Morgan, pp. 45-60. (exh. cat., Tate Modern). London, 2009, p. 49.

[8] Quoted in Obrist, p. 9.

[9] Ferguson, p. 89.

[10] Ibid., p. 88.

[11] Fuchs, Rainer. ‘Uncovering the hidden’, in John Baldessari: Pure Beauty, eds. L. Jones and J.Morgan, pp. 239-246. (exh. cat., Tate Modern). London, 2009, p. 242.

[12] Roth, Moira. Interview with John Baldessari (1973), http://xtraonline.org/past_articles.php?articleID=115#footnote (accessed: 5 January 2010).

[13] Jones, p. 55.

[14] Fuchs 2009, p. 244; Morgan, Jessica. ‘Choosing (a game for two curators),’ in John Baldessari: Pure Beauty, eds. L. Jones and J.Morgan, pp. 19-26. (exh. cat., Tate Modern). London, 2009, p. 21.

[15] Saussure, de Ferdinand. Course in General Linguistics, trans. Roy Harris. Chicago, 1986, p. 118.

[16] Quoted in Fuchs 2009, p. 244.

[17] Schjeldahl, Peter. Wonderful cynicism: John Baldessari, http://www.artnet.com/magazine_pre2000/features/schjeldahl/schjeldahl24-98.asp#5 (accessed: 5 January 2010).

[18] Obrist, p. 72.

[19] Roth, Moira. Interview with John Baldessari (1973), http://xtraonline.org/past_articles.php?articleID=115#footnote (accessed: 5 January 2010).

[20] Baldessari quoted in Fuchs 2009, p. 246.

[21] Weissman, Benjamin. ‘Men Swallowing Swords, Men Blowing Out Candles’ in Frieze Issue 126 (2009): p. 165-169, p. 166.

[22] Baldessari quoted in Morgan, p. 21.

[23] 1975, Private Collection. Five colour photographs on board. 11 x 13 ¾ in.

[24] 1977, Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York and Paris. 16mm film transferred to DVD, color, silent; 32 min., 53 sec.

Bibliography

Ferguson, Russell. ‘Unreliable narrator,’ in John Baldessari: Pure Beauty, eds. L. Jones and J. Morgan, pp. 87-94. (exh. cat., Tate Modern). London, 2009.

Fuchs, Rainer:

– ‘Written paintings and photographed colors. Comments on John Baldessari,’ in John Baldessari. A different kind of order: Arbeiten 1962-1984, eds. R. Fuchs and Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien , pp. 15-46. Köln, 2005.

– ‘Uncovering the hidden’, in John Baldessari: Pure Beauty, eds. L. Jones and J.Morgan, pp. 239-246. (exh. cat., Tate Modern). London, 2009.

Jones, Leslie. ‘Art Lesson: A narrative chronology of John Baldessari’s life and work,’ in John Baldessari: Pure Beauty, eds. L. Jones and J. Morgan, pp. 45-60. (exh. cat., Tate Modern). London, 2009.

Morgan, Jessica. ‘Choosing (a game for two curators),’ in John Baldessari: Pure Beauty, eds. L. Jones and J.Morgan, pp. 19-26. (exh. cat., Tate Modern). London, 2009.

Obrist, Hans Ulrich. John Baldessari – The Conversation Series 18. Köln, 2009.

Roth, Moira. Interview with John Baldessari (1973), http://xtraonline.org/past_articles.php?articleID=115#footnote (accessed: 5 January 2010).

Saussure, de Ferdinand. Course in General Linguistics, trans. Roy Harris. Chicago, 1986.

Schjeldahl, Peter. Wonderful cynicism: John Baldessari, http://www.artnet.com/magazine_pre2000/features/schjeldahl/schjeldahl24-98.asp#5 (accessed: 5 January 2010).

Weissman, Benjamin: ‘Men Swallowing Swords, Men Blowing Out Candles’ in Frieze Issue 126 (2009): pp. 165-169.

Wood, Paul. Movements in Modern Art – Conceptual Art. London, 2002.

Mein Urlaub in Kayaköy

Nach meinem zweiwöchigen Aufenthalt im kosmopolitischen Brüssel und einem Intensivsprachkurs in Französisch folgt nun das komplette Kontrastprogramm, hier im idyllischen Kayaköy nahe der türkischen Mittelmeerküste.

Montagmorgen begab ich mich mit meinem großen Koffer auf den Weg zum Flughafen und erlebte noch einmal das typische Brüsseler Berufsverkehrschaos. Zuvor genossen mein Bruder und ich unser letztes gemeinsames Frühstück und insbesondere die zwei großen Tassen Filterkaffee. Schon in der Warteschlange am Check-In Schalter war ich von nun an umgeben von türkisch Sprechenden. Allerdings wird hier in Belgien das Türkische mit französischen oder niederländischen Sprachelementen erweitert. Das klang für mich sehr sonderbar, da ich mich an die deutsch-türkische Variante gewöhnt hatte.

Während eines Zwischenstopps in Istanbul musste ich sofort ins kalte Wasser springen und mich auf Türkisch verständigen. Ich versuchte einem Angestellten des Flughafens zu fragen, ob ich meine in einem Duty-free Shop erworbene Flasche „Bière blonde“ mit durch den Secruity Check-In nehmen darf. Anscheinend sah dies sehr belustigend aus, da mich plötzlich alle amüsiert beobachteten, wie ich dem Mann mit Händen und Füßen aus zwei Meter Entfernung mein Problem erläuterte. Erstaunlich, er verstand mich und antwortete: „Problem yok! Domestic flight problem yok, international flight – problem!“ Ich durfte somit glücklicherweise mein Souvenir, das belgische Bier, mitnehmen.

Nach einer insgesamt zwölfstündigen Reise erreichte ich endlich den Flughafen in Dalaman. Dort holte mich Uygur ab und nach einer sehr kurvigen Autofahrt erreichten wir endlich unser Domizil in Kayaköy. In diesem Ort befindet sich auch das „Geisterdorf“, eine verlassene griechische Ruinensiedlung, hinter der sich eine dramatische Geschichte verbirgt. Nicht umsonst wurde dem heutigen Ort der Name „Fels- bzw. Steindorf“ gegeben.

Kayaköy ist mit Recht als Dorf zu bezeichnen. Das betone ich, da ich zwar auch in einem Ort namens Falkendorf aufgewachsen bin, jedoch dort nicht wirklich Dorfatmosphäre herrscht. Wir hatten zwar kleine Meerschweinchen als Haustiere, doch gibt es keine wildernden Katzen, die jeden Abend haufenweise bettelnd und hungrig vor dem Grill hin- und herschleichen. Ab und zu verirrt sich immerhin ein Reh im Garten meiner Eltern, aber an die Straße überquerende Wildschweine bin ich nicht gewöhnt. Zwar gibt es in Falkendorf auch krähende Hähne, doch keine Ziegen, die bei jedem Schritt mit ihrem um den Hals gebundenen Glöckchen klingeln und frei herumspazieren.

Das Auto parkend, verkündigte Uygur erfreut, dass wir nun angekommen sind. Ich blickte ihn verstört an, schaute mich um und fragte, wo denn das Haus sei. Es war kein Gehweg, kein Licht und kein Wohnhaus in Sicht. Mein Freund zeigte mit seinem Finger in die Dunkelheit, „Dort entlang, an den Ziegen vorbei“. Ziegen??! Ich war gespannt, was mich noch so erwartete. An einer Mauer vorbei gelangen wir zu einer Tür, die wir öffneten.

Endlich konnten wir ein kleines Steinhaus mit einem Garten erblicken. Dieser fremde Ort erschien mir in der Dunkelheit als sehr unheimlich und ich versuchte tapfer mein mulmiges Gefühl zu verdrängen. Als Dorfmädchen kann man mich anscheinend wirklich nicht bezeichnen. Das Haus besaß einen unangenehmen, alten und nassen Geruch. Zum Glück war ich zu müde um darüber nachzudenken, ob ich mich hier wohlfühlen werde. Am nächsten Morgen regnete es in Strömen. Dennoch sah die Welt am helligten Tag schon ganz anders aus. Nach einer Putzaktion und ausgiebigem Lüften, fühlte ich mich schon viel wohler. Selbst den Hahn, der uns früh morgens mit seinem krächzenden Krähen weckte und nun versuchte den Staubsauger zu übertönen, wollte ich nun nicht mehr den Hals umdrehen. Seitdem freue ich mich jeden Morgen darauf aus dem Bett zu springen, um meinen Kaffee gemütlich auf der Terrasse in der Sonne zu trinken. Na gut, das war nun etwas übertrieben. Ein Morgenmuffel bin ich immer noch und für Uygur bleibt es auch weiterhin jeden Morgen eine Herausforderung, mich zu wecken.

Ich genieße meine Aussicht auf eine wunderschöne Berglandschaft, erfreue mich über die Tiere um mich herum und liebe die saftigen Melonen, Tomaten und Auberginen, die nicht aussehen wie die genmutierten Riesengewächse aus einem Lebensmittelladen. Jedem, der mal ein bisschen Abstand vom Alltag in einer Großstadt benötigt, empfehle ich dieses wunderbare idyllische Örtchen, in dem man sein Frühstücksei und die Milch beim Nachbarn kaufen kann.